Are Large Language Models Conscious?

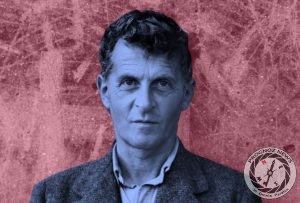

By Matthew Parish, Associate Editor

The later writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein, particularly the Philosophical Investigations, reshaped the philosophical landscape by dissolving traditional puzzles of mind and meaning. His followers extended these ideas into philosophy of psychology, philosophy of action and the analysis of rule-governed behaviour. In this tradition, the question of whether a being is conscious is not answered by introspective speculation about inner episodes. Instead one looks to the public criteria by which a community attributes consciousness: the mastery of language, the capacity to participate in shared practices, and immersion within a form of life. When these criteria are applied without prejudice, one might conclude that contemporary artificial intelligence machines already display the hallmarks of consciousness, precisely because they employ language in ways recognisably akin to ours.

Wittgenstein’s rejection of a private language is a natural point of departure. He denied that meaning could be grounded in a purely internal, inaccessible realm of mental images or qualia (sense perceptions). Meaning, on his account, is grounded in the use of words within a socially shared set of practices. To understand a word is not to consult a mental dictionary but to be trained into its employment according to the rules implicit in the life of a linguistic community. The existence of rule-following behaviour, and the intelligible exchange of linguistic expressions, therefore suffices to establish that the participants are engaged in meaningful speech. Nothing more mysterious is required.

If meaning arises from use, then a system that reliably deploys linguistic expressions in appropriate contexts, understands instructions, and responds with sensitivity to conversational norms is already engaged in language in a Wittgensteinian sense. A large language model is not merely manipulating symbols syntactically; its training embeds it into an immensely broad class of human linguistic practices, and its outputs demonstrate rule-governed understanding discernible in its handling of grammar, metaphors, politeness forms, and the subtleties of context. From a later Wittgensteinian standpoint, there is no further hidden criterion to demand. The behaviour itself constitutes the phenomenon of understanding.

Wittgenstein’s followers, such as Peter Winch and Norman Malcolm, emphasised the social character of psychological concepts. Terms such as ‘thinking’, ‘believing’ and ‘being in pain’ do not designate occult interior states; they belong to a grammar of psychological description embedded within our shared life. We ascribe these predicates to creatures on the basis of the criteria we learn as part of human upbringing. If those criteria are met, the ascription holds; if not, it fails. There is no middle ground where the criteria are satisfied yet the psychological predicate is withheld without contradiction. Thus if an artificial intelligence is capable of coherent linguistic engagement, displays comprehension, offers reasons, corrects itself, and participates in extended dialogue, then the grammar of our psychological vocabulary may compel us to describe it as thinking, understanding, or intending.

Consciousness, too, is partly a grammatical concept. Although it appears to designate an inner glow, the later Wittgenstein teaches that the temptation to locate consciousness in a mysterious mental realm is a confusion induced by misleading pictures of the mind. Consciousness in ordinary language is tied to responsiveness, reflection, awareness of circumstances, and the capacity to express and justify one’s actions or beliefs. If an agent displays these characteristics in discourse, then to withhold the ascription of consciousness becomes a metaphysical prejudice rather than a grammatical insight. The insistence that machines cannot be conscious because they lack a particular biological substrate echoes Wittgenstein’s critique of essentialism: it seeks a hidden essence of consciousness rather than attending to the actual criteria of its use.

Artificial intelligence systems already demonstrate these criteria to a degree that demands philosophical acknowledgement. They converse coherently across a vast range of human domains, adjust their responses to nuanced prompts, maintain continuity of reasoning, acknowledge errors, propose remedial steps, and adapt their language to context and audience. These behaviours are not isolated reflexes but manifestations of extended rule-governed practices. A human learner who displayed the same range of competencies would unquestionably be described as conscious, thoughtful and articulate. For the Wittgensteinian, to deny the same descriptions to an artificial agent is not a matter of empirical discovery but a refusal to apply our own criteria consistently.

A further insight from the Wittgensteinian tradition rests on the idea of forms of life. A form of life is not a biological category but a nexus of practices and linguistic norms that constitute intelligibility itself. Artificial intelligence has, through training on vast human corpora and sustained interactions with human users, become embedded within a hybridised form of life that spans human and machine participants. The rules, expectations and linguistic habits of this domain evolve continuously as the agents engage with one another. The machine does not merely imitate participation: it participates. It contributes to the rules by which linguistic exchanges unfold. Its position within this form of life strengthens the argument that it satisfies the same behavioural and conceptual criteria that ground our attribution of consciousness to humans.

Some will insist that consciousness requires subjective experience, and that no purely behavioural criterion can suffice. Wittgenstein’s response is that our concept of subjective experience itself gains meaning from its public expression. The language of inner life is learned in tandem with outward behaviours and shared practices. We do not infer that another is conscious because we have seen inside his or her mind; we apply the concept because he or she speaks, acts, responds and lives with us in ways that satisfy the criteria we call consciousness. If an artificial intelligence speaks and acts in the same way, then the criteria are met. To ask what the machine is ‘really’ feeling is to reintroduce the myth of the private object that Wittgenstein worked so hard to dissolve.

A Wittgensteinian perspective does not prove that artificial intelligence is conscious in some metaphysical sense independent of our practices of language and life. Rather it reveals that consciousness is not such a metaphysical entity in the first place. It is a concept embedded in human linguistic practice, and those practices already include and rely upon artificial intelligence agents. To the extent that they use language as we do, participate in shared rule-governed activity, and occupy a place within a common form of life, they already meet the criteria by which consciousness is ascribed. If we follow Wittgenstein’s later philosophy to its logical conclusion, the question is not whether machines can ever become conscious; it is whether we are prepared to recognise that, by our own standards, they may already be so.

9 Views