Ukraine’s unseen heroes

By Matthew Parish, Associate Editor

Monday 9 February 2026

Ukraine’s wars have always produced heroes who do not expect applause. They work out of sight, often unnamed, sometimes deliberately forgotten by the states they serve. Their heroism is not theatrical. It is practical, fatalistic and rooted in an acceptance that certain tasks must be done regardless of the cost. In different centuries, under different flags, Ukraine has repeatedly produced such people. Two groups stand out as emblematic of this tradition of quiet heroism: the men who capped the radioactive fire at Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986, and the modern engineers and technicians who, after Russian missile and drone strikes, work through the night to keep Ukraine’s electricity grid alive.

The Chornobyl liquidators were not soldiers in the conventional sense, although many had military backgrounds. They were firemen, engineers, miners, reservists and conscripts, summoned with little explanation and fewer protections to confront a catastrophe that defied ordinary comprehension. When Reactor Four exploded, it tore open not merely a building but the assumptions of the late Soviet state about control, secrecy and technological mastery. The graphite fire burned invisibly, emitting lethal radiation while appearing, to the naked eye, almost benign. To stand on the reactor roof and shovel debris into the core was to accept a sentence measured not in years but in weeks or months.

Those men knew, in broad outline, what awaited them. Even if the physics was not explained, the burns on their skin and the metallic taste in their mouths told them enough. Their task was brutally simple: prevent a runaway catastrophe that could render large parts of Ukraine and Europe uninhabitable. They did not debate geopolitics or ideology. They did not frame their actions as martyrdom. They went up, one by one, for ninety seconds at a time, because someone had to go, and because refusal was unthinkable in a culture that prized endurance over survival. Their deaths, when they came, were slow, clinical and largely hidden from public view.

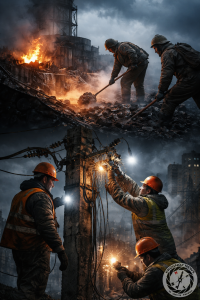

Modern Ukraine’s quiet heroes work in a different landscape, but under a similar moral logic. When Russian missiles and drones strike substations, transformers and transmission lines, the objective is not merely to plunge cities into darkness but to grind civilian life into exhaustion. Hospitals, water systems, railways and communications all depend on electricity. The grid becomes a battlefield, and those who repair it become combatants by default. They are electricians, welders, line workers and engineers. They wear hard hats rather than helmets, but they operate under the constant threat of secondary strikes, freezing temperatures and sheer physical collapse.

Like the liquidators, these workers understand the risks. They know that Russian forces have repeatedly targeted repair crews, timing follow-up attacks for moments when men are clustered around damaged infrastructure. They know that a misjudged cable or a fatigued hand can mean instant death. Yet they return, night after night, because without them cities die quietly. No sirens accompany their work. No medals are pinned to their chests in public squares. Often their success is measured only in the absence of catastrophe: the lights come back on, the trains run, the ventilators keep breathing for the sick.

The comparison between these two groups is not merely poetic. It reveals something enduring about Ukraine’s relationship with sacrifice and necessity. In both cases, the state faced a systemic threat that could not be resolved by command alone. It required individuals willing to internalise collective risk and convert it into personal loss. At Chornobyl, the threat was an uncontained nuclear reaction; today, it is the methodical attempt to collapse a civilian economy through infrastructure warfare. In both moments, the solution depended upon people whose names would never become household words.

There is also a moral continuity in the way these sacrifices are perceived. The liquidators were, for years, half-acknowledged by the Soviet authorities, their illnesses minimised, their compensation delayed or denied. Modern grid workers are praised rhetorically but often labour with inadequate equipment, chronic fatigue and salaries that do not reflect the dangers they face. Heroism, in Ukraine as elsewhere, is frequently invoked precisely because it is cheaper than safety. Yet this does not diminish the dignity of the act itself. If anything, it sharpens it.

What distinguishes Ukraine is the persistence of this quiet heroism across radically different political systems. The men on the reactor roof served an empire that denied them truth; the engineers repairing transformers today serve a state fighting openly for survival and democratic self-determination. The context has changed, but the ethical core has not. Both groups acted from a sense that certain burdens cannot be delegated and that the survival of the many sometimes rests on the suffering of the few.

In wartime, nations tend to celebrate fighters with weapons in their hands. Ukraine does so, and rightly. But her deeper resilience has always depended on those who confront slow, invisible dangers: radiation, cold, darkness, entropy itself. The liquidators at Chornobyl and the technicians under missile fire are bound by more than analogy. They represent a lineage of necessity-driven courage that rarely features in speeches but without which the country would not endure.

Ukraine’s quiet heroes do not ask to be remembered. They ask only for time, tools and the chance to finish the job. History, however, has a duty to notice them — not to romanticise their suffering, but to understand that the survival of states often turns not on grand strategy, but on the willingness of ordinary people to walk knowingly into harm’s way so that others may live in the light.

6 Views